Ready to learn more?

Get all the details straight to your inbox!

You can book a tour of Luther College, the U of R campus, and our student residence, The Student Village at Luther College, any time throughout the year. Contact our Recruitment Office at 1-306-206-2117.

Luther students can register in Arts, Science, or Media, Art, and Performance. Luther students are U of R students and receive a U of R degree.

Luther College students are U of R students and receive all the same benefits. Upon graduation you will receive a U of R degree.

Luther College offers Bundles programs that group together first-year students and classes to give you a great start and help ease the transition from high school to university.

Our student residence, The Student Village at Luther College, welcomes residents from ALL post-secondary institutions in Regina. Rooms come with a meal plan, free laundry, free wi-fi, and a great sense of community.

Luther College appeals to students who want to study in a safe, nurturing, and inclusive environment. We welcome students of all faiths, ethnicities, backgrounds, religions, genders, and sexual orientations.

Free enrolment counselling support and invaluable one-on-one academic advising are available for all programs at Luther College.

Smaller class sizes at Luther College means more individualized attention and better connections with your professors, classmates, and academic advisors.

Get all the details straight to your inbox!

By Brenda Anderson

Two fall events at Luther College offered our community some interesting insights into First Nations teachings that might contribute to our efforts in providing holistic teaching in the liberal arts tradition. At our annual Luther Lecture, Senator Lillian Dyck told her personal story of discovering her Cree-Chinese heritage and described the empowering sense this reclamation gave her. A week earlier, Luther College helped launch Kim Anderson’s new book Life Stages and Native Women: Memory, Teachings and Story Medicine in which a series of interviews with Aboriginal Elders showed that the power of “story medicine” throughout our four life stages (infancy, youth, midlife and elder) develops balanced and healthy individuals and community. Each academic activist has reflected on the usefulness of the medicine wheel in illustrating the different stages of life which parallel the different paths to accessing different forms of knowledge. What emerges in these reflections on personal narrative and on the medicine wheel is that the absence of voice or emotive, engaged learning leaves an unbalanced or fragmented approach to life.

Senator Dyck provided us with a type of knowledge not typically accessed through academic lectures. In telling about her mother’s and auntie’s method of escaping their Indian identity, which to them meant a life spent on a reserve plagued by deep poverty and the community trauma of losing children to a residential school, Senator Dyck raised larger questions about Canada’s colonial structure and the impact this has had on Aboriginal women across our nation. Revealing intimate details and photos about family members, recalling their advice to her as a young child to hide her Indian identity, and by relating how her perceptions of her mother as a victim changed as she learned about her story and saw that she was in fact every bit as strategic a survivor as herself, Senator Dyck engaged in a very old kind of knowledge, the knowledge of narrative, of story-telling. It is a knowledge of vulnerability and exchange. Senator Dyck risked the ridicule of those who haven’t experienced or heard about or perhaps even deny the colonialist framework of our country. Yet in that risk, a type of relationship can develop between the storyteller and her audience, for a request is also exchanged. If I dare to tell my story, do you in turn dare to tell yours? As I entrust these details to you, can you allow yourself to trust me with yours? This can be significant empowerment for many who have not considered they have anything worthwhile to say, who may have been taught to remain silent. To illustrate, during the reception after the Luther Lecture, some audience members told Senator Dyck about their respective mother’s escapes from their ‘Indianness’ by marrying “off-reserve.” Such an exchange holds potential for ever-widening circles of knowledge, healing and transformation, moments from which we can build community.

Similarly, Kim Anderson’s process of engaging Elders in story-telling was not only about capturing lost stories but is acknowledged as an act of reclamation or decolonization. Anderson writes, “We engage in a way of imagining a stronger way of life, one which belongs to us because it comes from our people and our past” (162). When considering racist governmental policies, social stereotypes and prejudices and lack of equity in Canada for Aboriginal people and women in particular, and juxtaposing this with the strong roles women typically played in cultures such as Cree, Anishinaabek and Métis, the significance of these stories becomes clearer. In the re-membering - bringing back the members of the community - and in remembering their stories and their knowledge, Anderson recreates a heritage of strength through which Aboriginal women might access their own stories and personal knowledge. Again, the stories create a model of vulnerability and exchange.

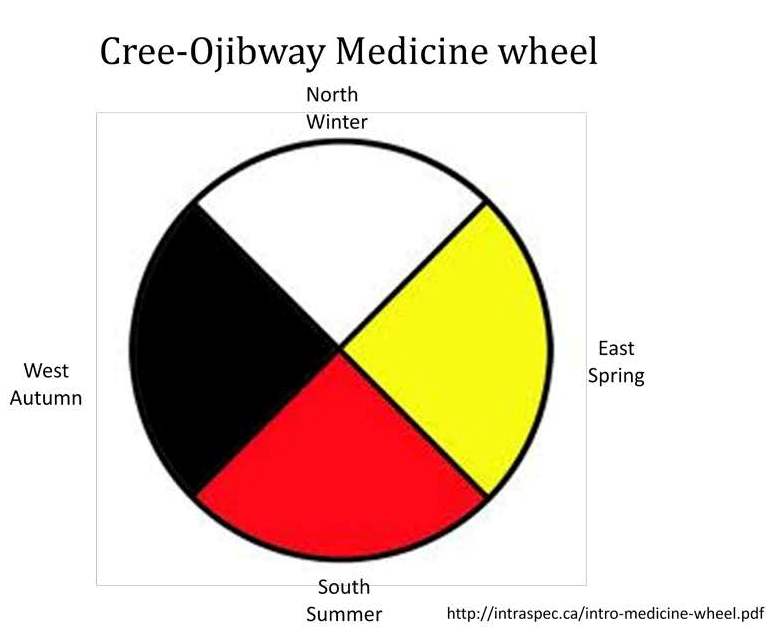

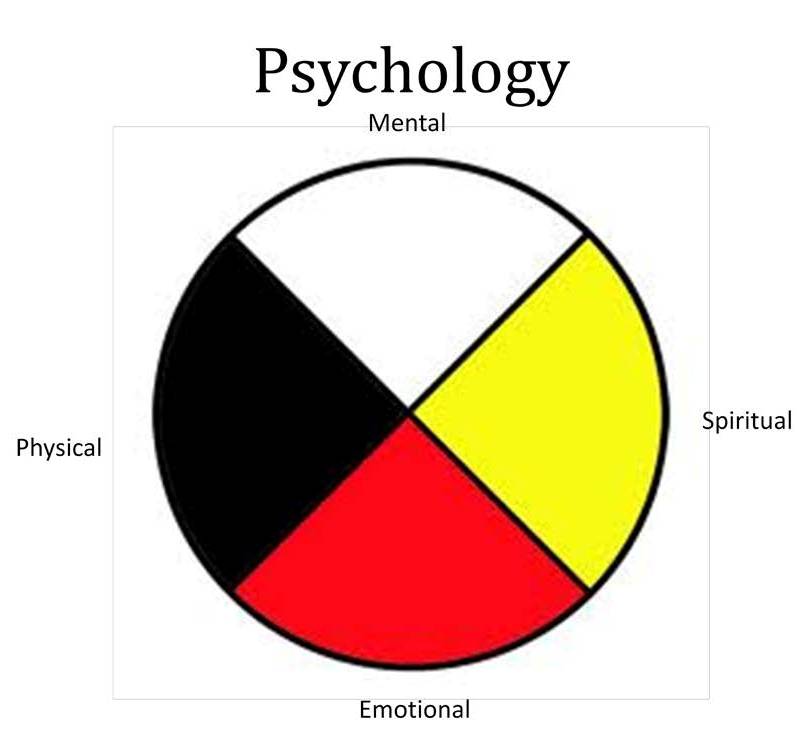

One tool Anderson uses in counseling Aboriginal youth is the medicine wheel. The overall philosophy is that at each stage of life, we are simultaneously expectant of and accountable to the community. The circular medicine wheel remind us of these life stages. The four quadrants, designated as the four directions – south, west, north and east – are connected to the four components of life – emotional, physical, mental and spiritual which are in turn linked to our four life stages – infancy, youth, middle-age and elder. At birth, we can expect to be cared for and in return we offer joy and gladness, laughter and hope. At adolescence, we can expect to be guided by the Elders into our adulthood, and in return we are accountable to the community by learning respect, a sense of connection and training in rituals and teachings. At mid-life, we become part of the guidance but we are most concerned with offering the material needs and providing for those who bring joy (the youth) and for those who guide us spiritually (the elders). At the final stage, the elders are cared for and are those who teach the traditions and are there both at the beginning “when the babies drop” and there at the end to help people transition to the spirit world. Each life stage brings with it responsibilities to the whole circle or community, and in return each stage can expect accountability, trust, and good treatment from the rest. This reciprocal relationship ensures continuity and a healthy, thriving community. Anderson has observed in her own work that it is this loss of belonging and accountability that has most significantly damaged the health of Aboriginal communities. Most poignantly, the Elders she interviewed for her book spoke of the soul of the community being ripped away when the children were stolen for the residential schools. They have yet to recover from this violence, she writes. When considered in light of the model of the medicine wheel, we can recognize how the community would crumble without the presence of the hopeful, youthful quadrant.

One tool Anderson uses in counseling Aboriginal youth is the medicine wheel. The overall philosophy is that at each stage of life, we are simultaneously expectant of and accountable to the community. The circular medicine wheel remind us of these life stages. The four quadrants, designated as the four directions – south, west, north and east – are connected to the four components of life – emotional, physical, mental and spiritual which are in turn linked to our four life stages – infancy, youth, middle-age and elder. At birth, we can expect to be cared for and in return we offer joy and gladness, laughter and hope. At adolescence, we can expect to be guided by the Elders into our adulthood, and in return we are accountable to the community by learning respect, a sense of connection and training in rituals and teachings. At mid-life, we become part of the guidance but we are most concerned with offering the material needs and providing for those who bring joy (the youth) and for those who guide us spiritually (the elders). At the final stage, the elders are cared for and are those who teach the traditions and are there both at the beginning “when the babies drop” and there at the end to help people transition to the spirit world. Each life stage brings with it responsibilities to the whole circle or community, and in return each stage can expect accountability, trust, and good treatment from the rest. This reciprocal relationship ensures continuity and a healthy, thriving community. Anderson has observed in her own work that it is this loss of belonging and accountability that has most significantly damaged the health of Aboriginal communities. Most poignantly, the Elders she interviewed for her book spoke of the soul of the community being ripped away when the children were stolen for the residential schools. They have yet to recover from this violence, she writes. When considered in light of the model of the medicine wheel, we can recognize how the community would crumble without the presence of the hopeful, youthful quadrant.

Each life stage contains within itself a certain way of accessing knowledge, each equally valued and necessary for the whole to remain healthy. Senator Dyck has engaged this question of missing quadrants to ‘Western’ institutional learning by reflecting on the medicine wheel. The four quadrants mentioned earlier might be applied to our four areas of a liberal arts education – the humanities (engagement), the natural sciences (fact), the social sciences (theory) and the fine arts (spirit). In the liberal arts model, each approach to knowledge and information is equally valued and necessary. Senator Dyck’s observations as a neurochemist is that the sciences in particular have missed the emotive or spiritual component of knowledge. The sciences have over-emphasised the value of fact and undervalued other means to information about our natural world. One might make the same observation about the other areas of liberal arts education. In any one of the four streams, missing a quadrant or an aspect of our whole way of accessing knowledge creates a gap. In particular, the exclusion of the personal or spiritual in our education, which includes the vulnerability and exchange inherent in personal story-telling, means the wheel is off balance and we are not offering our students the full potential of learning nor enabling them to apply their whole personhood to future endeavours. In Senator Dyck’s words, western knowledge is unbalanced because there is no Eastern door or spiritual aspect. We typically rely on the empirical and ‘factual’ without consideration of bias or intent. Nor do we engage our multiple ways of knowing. We in fact are frequently discouraged from applying other kinds of knowledge such as the personal/spiritual or holistic to our methods of enquiry.

The aim of both the liberal arts and the medicine wheel is integration and renewal of self and community. The emotional, physical, mental and spiritual aspects of our being are engaged, each in conjunction with the other. Each station on the wheel has its own significance, but the emphasis is on the whole. Completing the circle does not “end” the journey but moves to the next level.

The aim of both the liberal arts and the medicine wheel is integration and renewal of self and community. The emotional, physical, mental and spiritual aspects of our being are engaged, each in conjunction with the other. Each station on the wheel has its own significance, but the emphasis is on the whole. Completing the circle does not “end” the journey but moves to the next level.

We can think about the medicine wheel from a pedagogical perspective as well. The learner enters from the south, the quadrant of emotion. Unless there is emotional engagement, learning is likely to go no further, but to stop here is to become trapped in solipsism. Next one moves to the quadrant of fact, the physical world, the world outside of one’s self. Here the learner goes beyond “me and mine” and mere opinion to a grounding in empirical reality. But again, to stop here is to become ensnared in blinkered empiricism. The third stage is to move into the quadrant of theory, where one learns to discipline the mind, to make judicious generalizations, to gain perspective, to “make sense” of the world. The final quadrant is the spiritual, where the learner transcends him or her self. And having completed the circle one returns to emotional engagement, but now with a deeper understanding. In cyclical fashion, there is no true ending but rather a re-entering at a deeper level.

How we offer a liberal arts education at Luther College deserves an ongoing analysis. We hope to engage our students in all four ways of knowing. We strive to engage our students at a personal level, which is potentially vulnerable but also rich in possibilities of exchange and connections. We develop their self-awareness through contextualizing and theorizing the larger world and we teach them to be both expectant of and accountable to the larger global citizenry. Only with that sense of belonging and accountability can we expect students to take the risks necessary to live a full and balanced life.

How we offer a liberal arts education at Luther College deserves an ongoing analysis. We hope to engage our students in all four ways of knowing. We strive to engage our students at a personal level, which is potentially vulnerable but also rich in possibilities of exchange and connections. We develop their self-awareness through contextualizing and theorizing the larger world and we teach them to be both expectant of and accountable to the larger global citizenry. Only with that sense of belonging and accountability can we expect students to take the risks necessary to live a full and balanced life.

From the personal to the political, we see our roles as individuals and as institutions in both an expectant and in an accountable role. Senator Dyck’s reflections and Kim Anderson’s research reminds us of tools inherent within our own liberal arts tradition for moving forward in right relationship with the world as well as teaching us new/old ways of being. Personal story-telling, while fraught with risk of being misunderstood or ridiculed for principles often intentionally misinterpreted holds rewards and is worth our effort at Luther of modeling a principled and holistic life to our students. The reciprocal type of knowledge accessed through story medicine and the holistic, ever-deepening knowledge of all four quadrants of the medicine wheel, whether we use them to explain our four life stages or our four ways of accessing knowledge as represented in those four life stages would be fruitful additions to our list of best practices at Luther College.

____________________

Anderson, Kim. Life Stages and Native Women: Memory, Teachings, and Story Medicine. Winnipeg, Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press, 2011. Print.